The Enduring Legacy Of Gérald Genta And The Ingenuity Behind His Credor Locomotive, As Told By Evelyne Genta

Interviews

The Enduring Legacy Of Gérald Genta And The Ingenuity Behind His Credor Locomotive, As Told By Evelyne Genta

Summary

If we try to imagine a virtual Mount Rushmore of Horological Heroes that rescued Switzerland from the Quartz Crisis, there are certain names that are sacrosanct — such as Nicolas Hayek, with his creation of the Swatch watch; Jean-Claude Biver, with his resurrection of Blancpain; and the legendary Philippe Stern of Patek Philippe, who announced the return of complicated watchmaking with the Caliber 89. But one name that should occupy the absolute epicenter of any monolithic totem is Gérald Genta. His work was arguably the most vital, because it gave Swiss horology a new relevance during the immediate aftermath following the 1969 introduction of the Seiko Astron. More so, the very category of watches he created — the integrated bracelet sports-chic timepiece — is, to this day, the industry’s best-selling genre, speaking volumes of his everlasting legacy.

Looking back at the time when much of the Swiss watch industry viewed Japan with measured circumspection, it should be said that it was never Seiko’s intention to have any negative economic effects on Switzerland. The company’s focus was on quartz technology, which the Swiss were also pursuing, and this was an expression of spirited but fair competition. Let’s not forget that it was Swiss national Max Hetzel who invented the electronic tuning fork watch that eventually paved the way for quartz technology. However, when it came to industrializing quartz technology, the Swiss were one step behind.

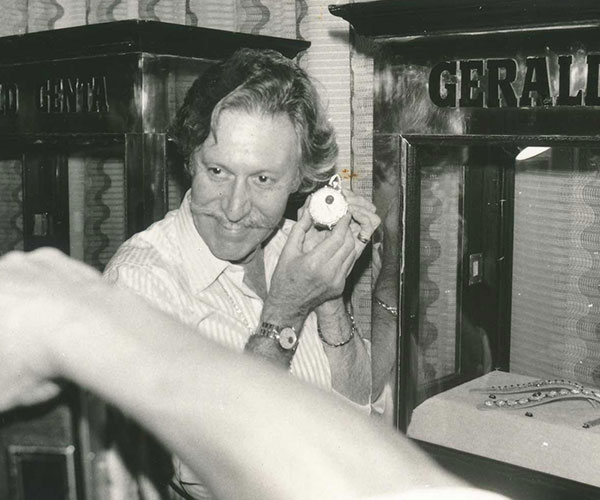

In the wake of the Quartz Crisis, the Swiss watch industry became increasingly concerned about the dominance of the Japanese in the global market. But not Gérald Genta, who found deep inspiration in Japan — his visits to Japan, in many ways, marked a turning point in his career. It was there that he gained the confidence to create his own brand, encouraged by none other than Reijirō Hattori, grandson of Kintarō Hattori, the founder of Seiko.

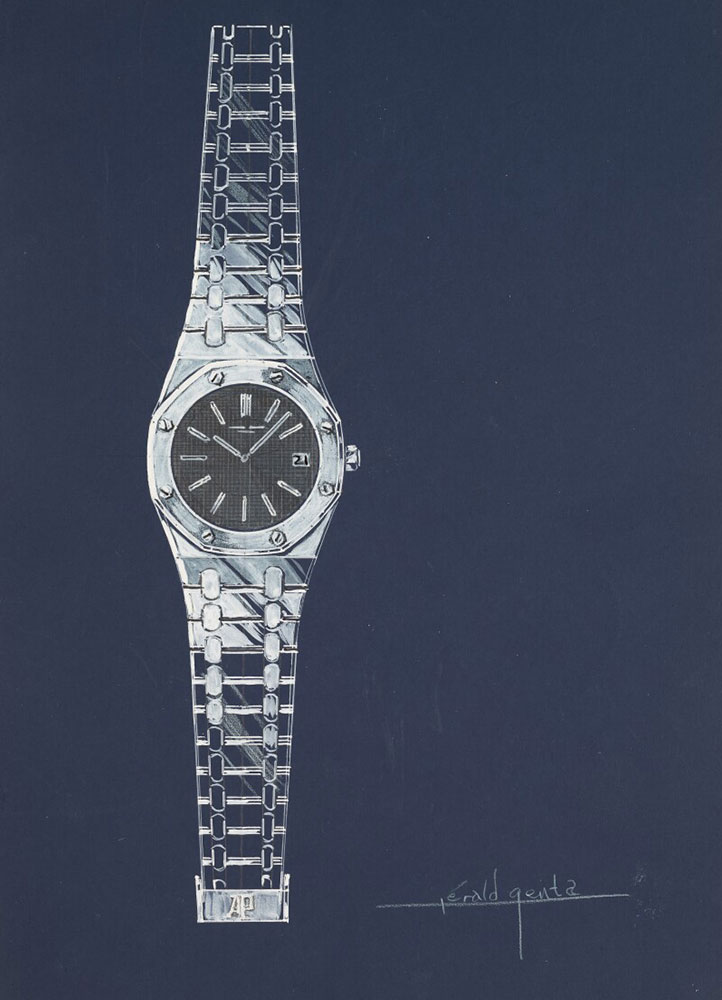

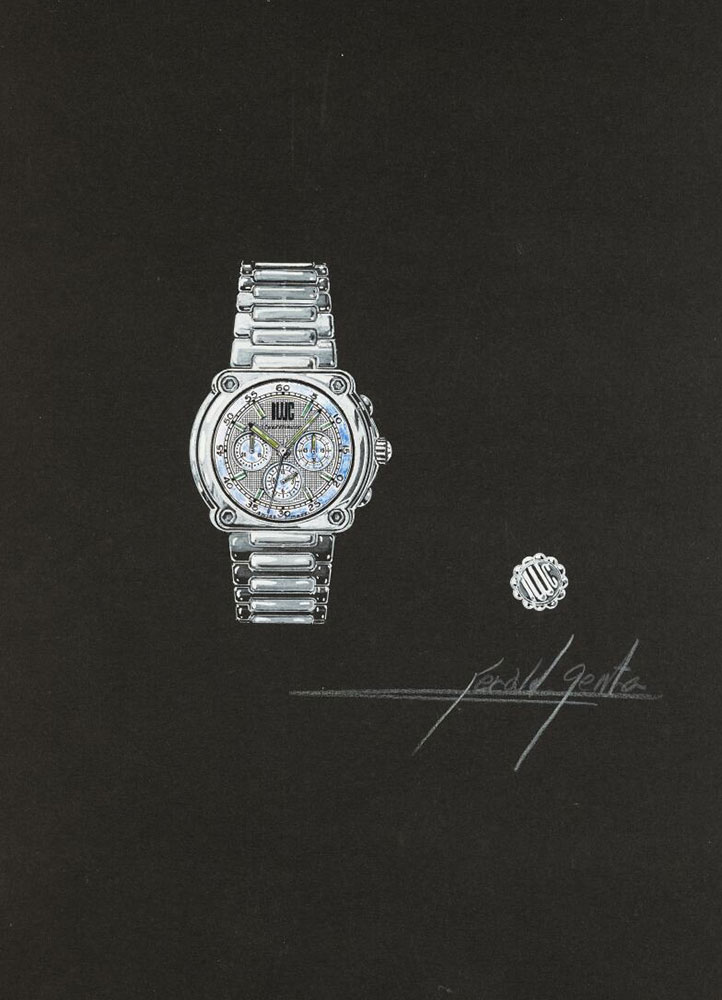

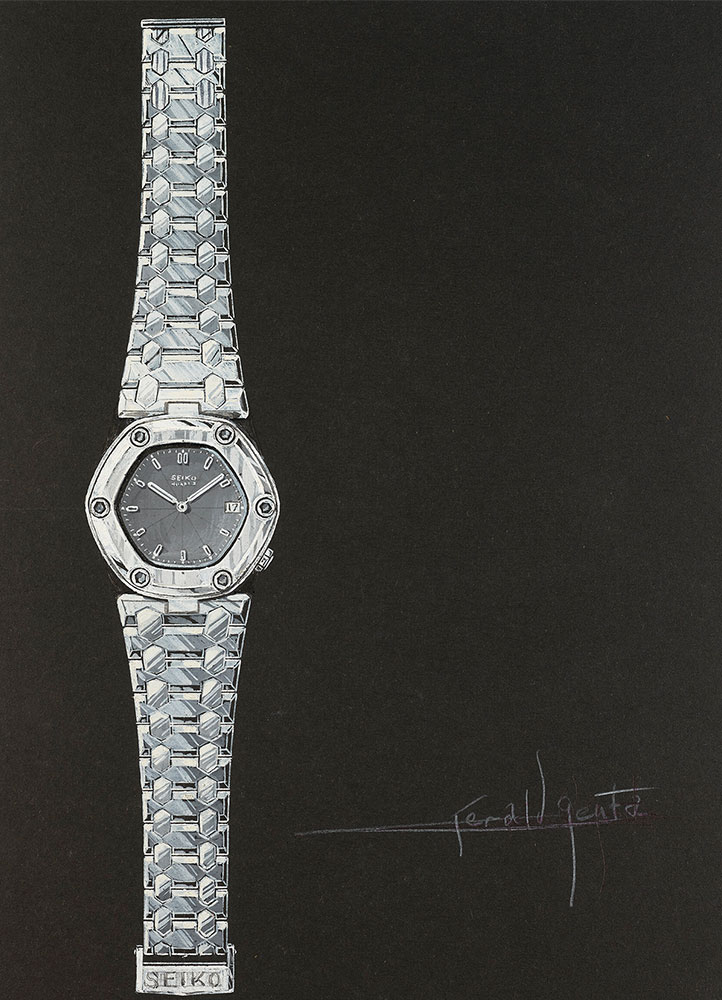

The watch that Genta created for Hattori’s second brand, Credor, which takes its name from Crête d’Or or “Pinnacle of Gold,” may well be one of his least known but most significant works. The Locomotive represented a gestation period marking his shift from working for others — creating watches such as the Universal Genève Polerouter (1954); the Omega Constellation (1959); the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak (1972); and both the Nautilus for Patek Philippe and the Ingenieur for IWC (1976) — to formalizing his vision for his own brand. As such, the Locomotive was the perfect symbol of the juxtaposition between Genta’s past and his future.

- Original prototype design of the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak, circa 1972 (Image: Sotheby’s)

- Original prototype design of the Patek Philippe Nautilus with two suggested case profiles, painted by Gérald Genta, circa 1976 (Image: Sotheby’s)

- Original prototype design of a bracelet watch for IWC, circa 1975 (ImageL Sotheby’s)

At first glance, it appears to be an integrated bracelet watch, something he was famous for, yet upon closer inspection, it also defies that categorization. Like the timepieces he would make under his own brand, it has a center lug which allows the intricate bracelet to become a framing device for a shaped watch head.

I had, of course, noted the relaunch of the limited edition Locomotive by Credor last year to mark the 50th anniversary of the brand. But it wasn’t until this year, when I attended the Paris launch of the new regular edition Locomotive and put the watch on my wrist that I fully experienced the emotional power of the timepiece rendered in high-intensity titanium.

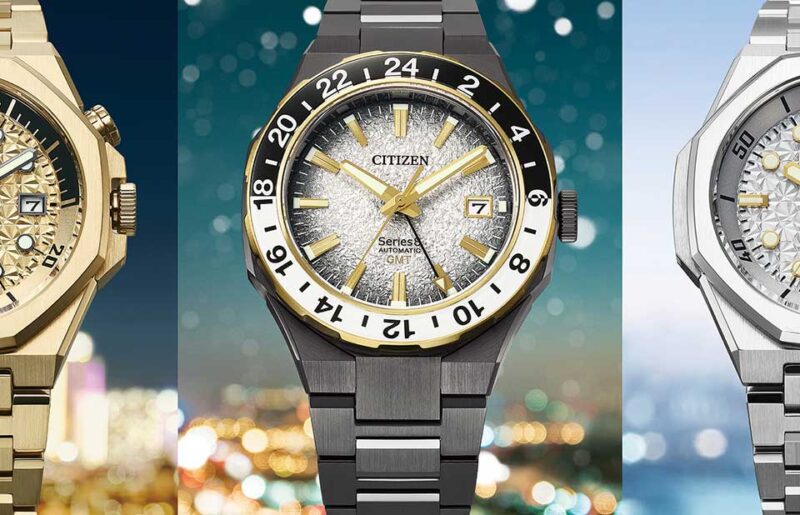

- Original Credor Locomotive designed by Gerald Genta in 1979

- Credor Locomotive GCCR999 launched in 2024

- New Credor Locomotive GCCR997, 2025 edition

The proportions of the watch at 38.8mm in diameter and 8.9mm in height were perfect. The special dial, featuring a honeycomb motif with striations in each segment oriented in opposing directions to reflect light differently, was wonderfully imaginative. As a result, even though the entire dial is a uniform shade of forest green, it appears to your eye as contrasting sections of light and shade. What I was most impressed by was that the Locomotive remains Genta’s most purposeful and unique execution of formed art for the wrist. It is a watch, of course, and functional in every way, but it is also a personal take on sculpted time-telling jewelry.

As such, it became the perfect remedy for the integrated bracelet watch ennui that I suffer from, along with many of you. The Locomotive is so charmingly unique that you can’t help looking at it over and over again on your wrist, and all of this is down to Genta’s creation of a brilliant dynamic tension between the shaped, almost ornamental watch head just barely attached to a powerful and complex bracelet and the negative space that separates rather than unites them.

The choice of high-intensity titanium for the limited edition released in 2025 was a cool move, bringing the Locomotive into our time (Image: Revolution ©)

Intrigued, I sat down with Genta’s wife and business partner, Evelyne Genta, to learn more about the watch and the genius who created it.

Why was Japan so special to your husband?

Mr. Reijirō Hattori was at the very start of Gérald doing watches for himself. Of course, he had done many famous watches for other brands. But you must understand that Gérald came from a very poor background. I would describe [the conditions he grew up in] as something from a Dickens novel. And so he never had the confidence to go and make his brand amongst the aristocracy of horological luminaries.

Today, the young watchmakers and brands are so confident. They say, “Well, I’ll make three here and five there, and I’ll sell them for 500,000 dollars. And you’ll be lucky if you can have it, but you have to first be on the waiting list for two years.” Back in his time, it was unheard of for someone to just create their brand.

Probably on some level, the entrenched leadership in the watch industry didn’t love the idea of the man who had designed watches for them starting his own brand. But Gérald had a revelation when he went to Japan. He loved it there, and he had already done many watches for Seiko before working on Credor. When he met with Mr. Hattori, something changed for him. They were like two long-lost friends, very much in sync. Probably Mr. Hattori appreciated him as a Swiss designer working with him. In that era, as a result of the Quartz Crisis, the Japanese were looked upon as “the enemy” by the Swiss. But Gérald loved Mr. Hattori because he was such a gentleman.

So this was the genesis of the Gérald Genta brand?

Yes. Gérald showed some samples and designs, and Mr. Hattori replied that rather than make them for him, Gérald should showcase them under his own name. Mr. Hattori even helped him with an exhibition at Wako department store in Tokyo. Because there was not so much awareness of his name, they billed him as the guy that had done “this and this watch” for other brands. Then one of these brands phoned Mr. Hattori to complain. Mr. Hattori was quite shocked because, in Japan, there is real reverence for designers and creators. So he went to Gérald and said, “Put your name on the dial of the watches and create your own brand — you deserve it.” So you see, Mr. Hattori gave him the confidence to become Gérald Genta the brand. That’s why his affection for Japan, Seiko, Credor and Mr. Hattori is so significant to us.

I consider your husband to have played a huge role in saving Switzerland from the Quartz Crisis. What’s your take?

I think in some ways, through his creations for other brands, Gérald helped to save the Swiss watch industry. The watch industry was really in peril in the ’70s. They were closing one factory after another. There was this very real sense of peril. But Gérald always felt that if you have talent and craftsmanship, then you have to express it. At the time, the Swiss industry was trying to react to the changes by introducing their own quartz movements into watches, which was not really their core DNA. Gérald had nothing against quartz and even used it in ladies’ watches, as he felt women wouldn’t want to damage their fingernails [by winding a watch]. But he felt that if you have talent, then you have to use it when times are tough. He had nothing against Japan and, in fact, felt there should be an open dialogue between East and West.

You spent a lot of time in Asia. Why?

Asia was always a second home. Singapore and our partnership with The Hour Glass were important to us. I remember Michael Tay was eight years old when he came to our wedding. Brunei and Malaysia were, of course, of immense importance too. So Gérald always was very comfortable in Asia. I think it took the rest of the Swiss [watch industry] a little bit later.

The industry is stuck in a pretty significant downturn today. What would your husband have done to help combat this, if he were here?

If Gérald were here today, he would not be concerned about the Apple Watch or AI. He believed with his whole heart in the power of beauty, and that beauty comes from human beings. He believed very much in the emotion generated by craftsmanship, and that no one could replace these incredible individuals that create timepieces with their hands.

He loved to watch someone bending the overcoil on a hairspring many times thinner than a human hair. He loved seeing a watchmaker do a double assembly. Putting the watch together first to ensure it functioned correctly, then totally disassembling it and finishing each surface before assembling it again. We have had so many crises throughout human civilization, but he would ask, “Did any of them remove art?” No, none of them did. So he was never fearful even when things were tough. He felt motivated to create beauty in these situations.

The watches he created 50 years ago are still the most popular models today. Would this have pleased Gérald?

Yes, I believe so. It is quite remarkable that the category of watches that my husband created over a half century ago in 1972, is still the dominant form of wristwatch today. You know, he created thousands of designs. There were all those uncredited ones, because when he was young, he would sell whatever he could. When he was 22 or 23, he would travel to La Chaux-de-Fonds, La Côte-aux-Fées and Le Brassus, and he wouldn’t come home until he had 3,000 Swiss francs in his pocket. So we have no idea about the full scope of what he created. I wish we knew because, unfortunately, he never kept archives.

We have at LVMH Gérald Genta Heritage over 4,000 designs showcasing his creativity. The way he worked was never to respond to a brief. It was never, “Well, Mr. Genta we feel the trend today is such and such.” At Basel fair, people would ask him, “Have you seen the Concord or the Corum?” but he really wasn’t interested in trend. He either felt it or not.

With Seiko, there are rules; with Credor, it was open. Was that the attraction to working with Credor on the Locomotive?

I think he felt that Japan had something incredible in terms of the quality of its steel. So he definitely wanted to use steel. He wanted to do something really different because, for him, Japan was like a different planet, but one he loved. So he decided he wanted to do a hexagonal watch. There are almost no hexagonal watches in his vocabulary. Octagons are prevalent not only in the work he did for others, but also for himself. But for Japan he thought a hexagonal [shape], which is close to a circle but with facets, would be very elegant.

What is one thing people don’t know about your husband?

People love his designs, but they don’t realize how complicated technically they are to execute. The bracelet on the Locomotive is stunning, but it is extremely complicated and very difficult to create. He, of course, knew everything about bracelets, because he got his start as a bracelet designer at Gay Frères. He knew how to build them; he knew how to build a watch. He could explain to the machinist how to create each piece. This skill set allowed him to create formed art for the wrist.

What is the beauty of the Locomotive to you?

There is nothing superfluous on the Locomotive. Everything is useful. If you remove the screws, the case comes apart. I remember a jeweler once asked him, “Mr. Genta, how many diamonds are on your watch?” And he replied, “The number that is necessary, not more and not less.” As an amusing aside, that same jeweler wanted to buy this watch from Gérald. He kept asking how many carats, and eventually Gérald got fed up with him and said, “You know, sir, when you want to buy a Picasso, you don’t ask for the cost of the paint.”

The bracelet design is important to Genta’s legacy as he got his start as a bracelet designer at Gay Frères (Image: Revolution ©)

There is a very special dynamic contrast within the Locomotive that my husband was very proud of. The watch is simultaneously an integrated bracelet watch but also not integrated. He initially designed the watch as a fully integrated bracelet timepiece with a kind of barrel case, hexagon bezel and this lovely bracelet. But the more he looked at it, the more he wanted to do something different. The separation between the head of the watch and the negative space in between creates a delicious tension. The bracelet acts like a framing device for the watch, and the two elements are necessary to each other, but at the same time, a bit individual.

This also gives the wearer the option to wear the Locomotive with a strap, whereas for my husband’s other designs with the bracelet and watch created as one piece, I am not so sure.

How did Gérald design?

I loved my husband’s design process. He would wake up super early, even on a holiday or the weekend. He would always dress in a suit and tie, no matter what. He would sit down and put music on. He had pieces of blue paper and would start with a compass, draw a circle, then take a ruler and draw two lines. Then using very fine paintbrushes and watercolor, he would paint the watch from beginning to end almost without stopping. If you look at a Genta design, it is painted, never sketched. He just painted. I asked him, how do you do this? He replied, “Because it comes to me as one.”

According to his wife, Evelyne, Genta always painted his designs instead of leaving them as sketches

I remember seeing photographs of the great American painter Jackson Pollock create his drip paintings from beginning to end, as if guided by the divine, and it was the same with my husband. I think this is a bit of genius. It poured forth from him, and he didn’t know why. Remarkably, he would design the Locomotive, and then the same day, he could design a ladies’ watch. It wasn’t like he was stuck on sports watches for three months. Not at all. He had this amazing capacity to switch back and forth.

Why did he name this watch the Locomotive?

The Locomotive was one of the very few watches that he named. He felt that a locomotive is something of a double entendre. It is, of course, a railway engine that was a key driver of modernity in the 20th century. It symbolizes a dynamic or seismic shift in culture, representing a big move forward. At the same time, in French, it is in music, the song or record that is a big hit. You would say, “Oh my God, that album is such a locomotive.” So Gérald played with these two meanings.

What do you feel when you wear the new Locomotive on your wrist?

The Locomotive is a watch that represents a burgeoning new decade filled with promise, optimism and hope, as the ’80s were. I think there is this lovely optimism in this watch. So when I wear it, that’s what I feel — optimism.

Do you recall getting the call to bring back the Locomotive?

When Credor asked me, I said yes right away. In 2021, Mr. Naito approached me and I immediately wanted to do it. The litmus test for me was, would Gérald have liked the idea? Actually, Gérald was very instinctive about people. He would have loved Mr. Naito a great deal, in the way he would have loved Jean Arnault. He would be happy that they both appreciated art in a big way. Our favorite clients care for authenticity and beauty. They don’t have one eye on the stock exchange; they have real love for watchmaking.

Do you feel that major watch brands today are like movie studios making the same superhero movie over and over? And that it is brands like Credor that are bringing real creativity?

Yes, that’s it — superhero movies, indeed. Once we have one, let’s just keep remaking it over and over. Then you have something like the Locomotive that has such a powerful originality and singularity to it. I must commend the designer at Credor who brought the watch back to life, for the sensitivity with which he reconnected my husband’s work to the modern world. They got the proportion and size perfect.

The deep green dial comes across as two shades of forest green, delightfully rendered in a hexagonal pattern with the striated pattern with shapes that alternate in direction (Image: Revolution ©)

The thing about the Locomotive is that it is such a striking and unique design that can be quite bold. But at the same time, it has an inherent elegance. It fits perfectly and comes alive on the wrist, but is thin enough to slip under a cuff effortlessly.

What did Gérald love most about Credor?

There was an interesting article that came out recently that said the future of luxury is handmade. I certainly hope so, because otherwise human beings will become obsolete.

“Remarkably, he would design the Locomotive, and then the same day, he could design a ladies’ watch.”

When I look at the Locomotive and see how intentionally hard it is to execute, how much it requires a human being to make this, it is reassuring. You see, Japan is one of the last refuges of true handmade, and my husband clearly understood that. He loved how when things are broken in this culture, they are repaired with gold, which ennobles them.

The first version of the Locomotive, the limited edition, had a dial that featured 1,600 individual lines and felt so alive in the light. The same with the dial on the regular production version. You think that its honeycomb pattern is composed of contrasting light and dark shades of forest green. But it’s actually the clever use of the pattern in each section that creates a darker or lighter effect when reflecting light. So the dial is actually all one color, but the arrangement of the stamped pattern with each section is what creates this dynamic interplay of light and dark that ripples across the dial. Gérald would have loved this.

Also, take a look at the level of finishing — the perfect mirror polishing on the bevels of the bezel. My husband used to say, “The level of the anglage at Grand Seiko [is higher] than anything in Switzerland.” The watch is really quite sublime.

Credor